ONE – Arrival

Robert and I arrived in Chamonix on Saturday, the last rainy day before a week-long good weather window. According to everywhere, Monday to (at least) Friday were meant to be blue-bird sky, windstill, warm and storm-less days. Unsurprisingly, we were both incredibly psyched to do some major ‘ticking’. However, the mood wasn’t to great when we arrived…

Independently, Robert and I had thought up a list of routes we would like to do. Comparing them in the car was equally hilarious and freakish, since they were nearly the same. They went something along the lines of:

Tournier Spur, Droites

Innominata Ridge, Mont Blanc

Cordier Pillar, Grand Charmoz

Swiss Route, Grand Capucin

Küffner Ridge, Maudit

Arete de Diable, Tacul

etc…

Being on the top of the list for both of us, and having heard there were good conditions, we decided to aim our efforts at the Tournier Spur on the Droites north face. In the car, I called the Argentiere hut to ask about conditions. The call shattered our hopes. Despite having to speak french, I managed to understand that the hut guardian strongly discouraged any attempt. To our surprise, a team had completed the route a few days back and reported terrible conditions on the upper mixed section. A call with the OHM in Chamonix didn’t help the situation. They knew of no ascents in the north faces of the Argentiere basin throughout this summer.

Of course there were the other routes on the list. The Innominata ridge had been on my mind for quite some time. Conditions were reportedly perfect, but there were two problems: Firstly, being in a popular area, the Eccles bivouac and the ridge would be completely overfilled. Secondly, we would have to top out on Mont Blanc which would be a struggle in our un-acclimatised state. Of course these are rather superficial issues which we could have dealt with, but we had mentally prepared for a north face struggle and were now looking for an appropriate alternative. Consequently, the other routes were dismissed with similarly poor excuses…

It was while flipping through the guidebook that we came across another mutual wishlist route: The Croz Spur on the Grandes Jorasses north face.

Robert had already climbed the Walker Spur and had since been keen to give the neighbouring Croz Spur a go as well. The route was thus genuinely on his list. For me, the situation was a little different.

I have wanted to climb the Grandes Jorasses north face for a while – usually dreaming about climbing the Colton-Macintyre. The wall is huge, notorious and somehow seriously tempting. Its a combination of its legendary status (one of the big three north faces in the alps, etc, etc), the epic adventures had therein and the reportedly fantastic lines that make it every alpinists dream. But for most – and myself included – it is nothing but a dream. Having read so much about the face, I was sure I wasn’t going to attempt anything like that for a few years. The wall is just too big, too difficult and I am too inexperienced. Even the ‘relatively easy’ Walker Spur seemed far away. The Croz Spur was thus not really on my list, but the wall was definitely on my mind. But being in Chamonix with Robert the cards had changed a little. I was as fit as I’ve ever been and none of the recent routes had felt particularly at my limit. Physically, I thought I could give the Grandes Jorasses a good shot. Secondly, being there with Robert was probably as good as my chances would ever get. We had seen on the Cassin that we climbed well as a team and, being seriously experienced, he was a great partner for such an undertaking. It was a combination of those reasons and my desire to climb the Grandes Jorasses that made the Croz Spur appear on my list as well.

I called the Leschaux hut, half hoping to hear conditions were bad, half hoping to hear the opposite. The phone call was quick, and our north face dreams were instantly reignited. The guardian had essentially said that she thought the route was in decent condition and climbable. Robert and I didn’t need to hear more.

After starting our Chamonix ‘holiday’ by climbing “Poème à Lou” on the Brevent on Sunday morning, we headed back to the campsite to finalise our decision. We would walk in to the Leschaux hut on Monday and check out the conditions. If the Croz Spur looked good, we would try it. If not, we would go for the escape option and climb the Petites Jorasses west face – a stunning 900m granite rock route. In the Croz Spur case, we would try the route starting from the hut on Tuesday morning, plan on having to bivouac and then descend to Italy on Wednesday if we were successful. Robert and I were happy with the simple, but significant plan. The rest of the evening was spent carb-loading with pasta and looking for trip reports and topos of the Croz Spur. I found quite a lot, though none of the ascents had happened in summer…

Two days before hopefully starting, I went to bed anxious, but very happy that I would be able to try a large north face after all.

TWO – The Route

A little aside about the route.

The Grandes Jorasses north face as seen from the hut on Monday.

The Croz Spur is the central spur on the Grandes Jorasses north face. In 1935, it was the first route to be climbed on the whole wall. The two Germans Martin Meiers and Rudolf Peters succeeded after having tried and failed the year before. Once again, the initial failure was accompanied by the death of another climber in their team. Though arguably the more important climb, the Croz Spur soon became neglected when Riccardo Cassin opened the Cassin on the Walker Spur. For most people, the Walker Spur is the first route to climb on the face. The Croz spur sees far less ascents.

The Grandes Jorasses North Face guidebook describes the route as:

“Historic route, a long, varied and interesting mountaineering route.”

Quite the understatement in my opinion.

Topo from the Grandes Jorasses North Face guidebook. The Croz Spur is route number 29 and actually climbs the right hand side of the spur, passing through the two snowfields.

Today, the route gets the following grades, although they’re obviously highly conditions dependent: 1100m, ED1, WI4, M6+, 5c. The Croz Spur is supposed to feature much easier rock climbing than on the Walker Spur, however, it is also supposed to be far more difficult in terms of the ice and mixed climbing. Nonetheless, the Croz Spur is one of the easiest lines on the Grandes Jorasses north face.

When you google the route, most accounts describe the Croz Spur with the Slovenian start. That is the most common way to climb the spur today and is apparently a great ice route, if only climbable in winter.

The summer descriptions I found are limited. There is merely a bit of talk of loose rock and that the final headwall has stumped quite a few teams (involving some helicopter rescues). So back to my account…

THREE – Day 1

Monday morning was the time for scrutinous packing. Besides the route, weight was our main enemy. Each bit of kit was assessed in terms of its weight and use. We rebuilt quickdraws, ripped pages from books, adjusted axes, emptied first aid kits, exchanged slings and much more, to save every last gram. In the end, our climbing rack was large – it had to deal with ice and rock – but light. Our bivouac gear was minimal – a two man bivy bag and a stove – and cold. Our food was too little – maybe a grand total of 1500kcal each – but light. And our clothes were hopefully just right – would two down jackets suffice as a sleeping bag? We packed it all up and in the end probably had around 16-18kg backpacks. Heavy. Too heavy. Another round of unpacking, scrutinising and re-packing followed, but we couldn’t eliminate anything. The weight stayed constant and our hearts sank a little.

Almost all of the gear we took.

As the time drew closer to leaving the campsite I became ever more anxious. Quitting now would be so easy.

I got changed and put on my big boots in the sweltering heat. My feet were sweating instantly.

What the f*** was I doing?!

I got in the car and started up the engine. Rolling out of the campsite a wave of relief swept over me. The trip had basically started and the temptation to quit was fading as quickly as Argentiere was disappearing in the rear view mirror.

We bought a one way ticket up to the Montenvers train station and boarded a train at 12:30. It was packed and noisy, but I wasn’t really aware of anything. All of my focus was on what lay ahead. It would possibly be the best, but possibly the worst decision I would make.

The view towards our objective.

The Dru in its full might.

We left the top train station and the obnoxious people behind as fast as possible. Luckily, the thought of being alone on a glacier was more comfortable than being herded around like cattle at Montenvers – quitting was no longer on my mind. The hut approach was long and tiring and the heavy backpacks dug into our shoulders. Adding to the anxiety, the face we wanted to climb seemed to grow with every step. Almost unexpectedly, all those routes I had read and dreamt about were towering above me, ready to swallow me whole. Before climbing up to the hut, Robert and I studied the wall. It actually looked good! The rock sections seemed to be dry and all of the mixed sections seemed to be white. In fact, we were surprised by just how good it looked!

The final ladders up to the Leschaux hut were unforgivingly long, but we made it at some point. Arriving on the terrace delivered a sight I will never forget. The hut guardian was sat looking at the Grandes Jorasses through her telescope, on the phone, explaining directions in broken English. Two Koreans had gotten lost without a topo on the Walker Spur and had called the hut to ask where to go.

The Grandes Jorasses north face from the hut.

It was the first time that I started to think that I may actually be ready for such an adventure. I mean, if people like that are trying the Walker Spur, then surely I could do something easier!?

At the hut we studied the guidebook and the face through the telescope. The bergschrund seemed large, but – after some consultation with the guardian – seemed passable on the left of a large rock. The next snowfields seemed easy and covered in névé. The gully behind the two towers was probably dry, but easy to find in the dark. The rock on the spur looked very dry and easily climbable. The snowfields sadly looked very blank, and we would have to pitch across them. Finally, the upper section looked dry, but cold, so the original exit would be the best. Generally, Robert and I agreed that the wall was in good condition. The Petites Jorasses were dismissed.

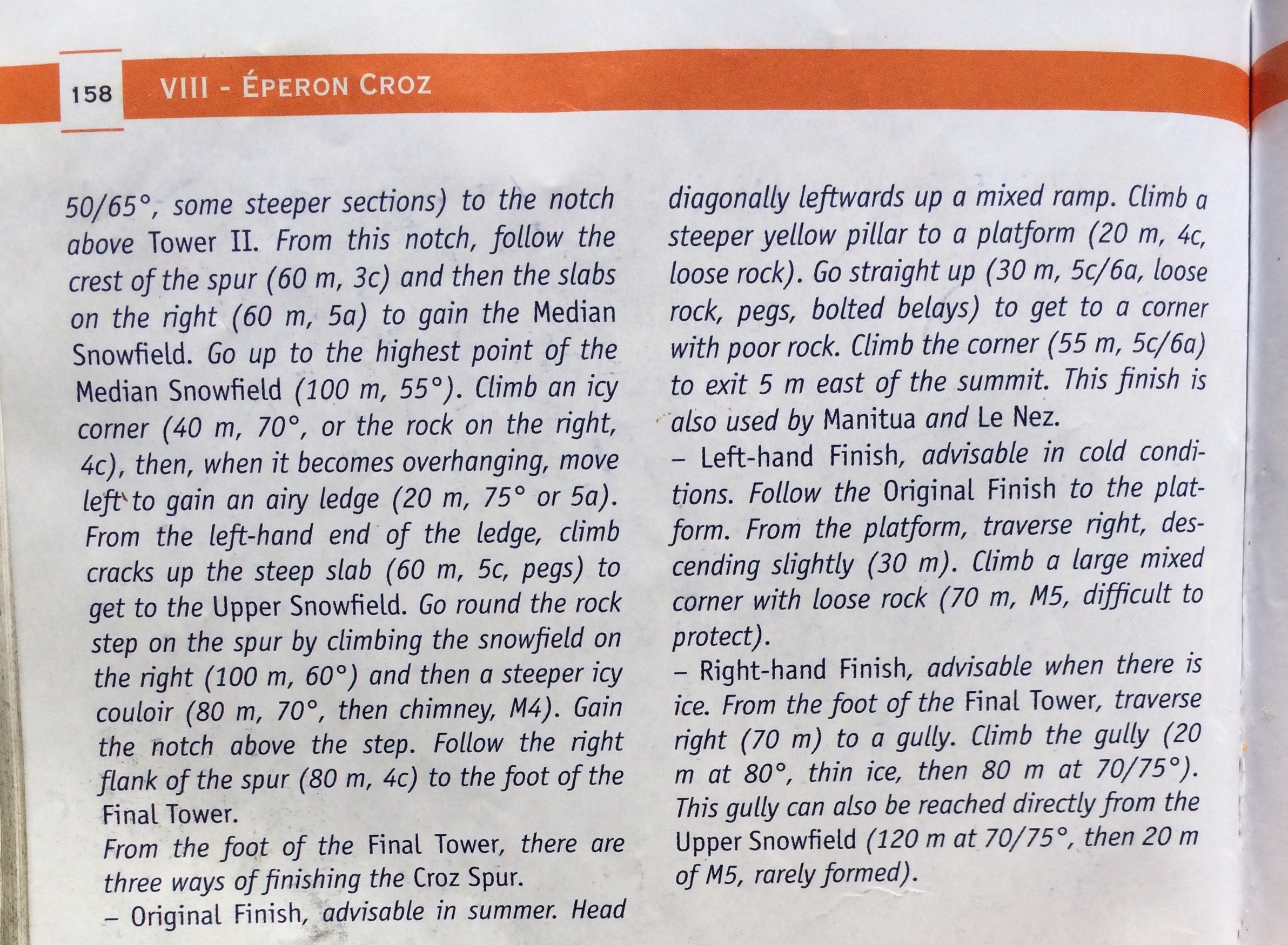

Description of the Croz Spur.

Before dinner, one of the guys at the hut came over to us to tell us about his own Croz Spur adventure. He had tried the route a long time ago, but had to get rescued by helicopter just 20 meters below the summit. During their ascent the rock in that section was simply too loose and dangerous to climb. He said it had been too dry and warm then, but it seemed like it would be much better now. “Bonne chance!”

At dinner, we saw who would be joining us in the morning. There was a team of four French, and two Irish, all of who would attempt the Walker Spur. We would be alone on our ascent, but at least we were not the only ones thinking the wall was in good condition. Bags packed and ready for the 1am wake up, we all went to bed.

FOUR – Day 2

I was surprised that I woke up at 1am, since I had thought that I wouldn’t fall asleep. There was an awkward tension at breakfast: the four french joked around, the rest of us were silent. It was clear that everyone was apprehensive about the unknown that lay ahead. I managed to shut out my worries by focusing on the things I had to do: eat, drink, get dressed. Simple. We were out the door by 1:30 and on the glacier not long after that. It was a fantastic night. The moon was so bright it cast a shadow, allowing us to approach the wall without headtorches. Even the gigantic crevasses were light enough to be seen – and subsequently dodged.

To our great relief the Bergschrung was easy to pass. We had now started the route and I was starting my biggest adventure yet. It was just past 3am. We had made good time.

After an easy plod up the snowfield we stopped to rack up on a rock outcrop. The ramp above looked easy and our spirits were high, since everything had run smoothly so far. I was secretly still hoping to top out that evening! The ramp wasn’t hard, but in the dark it was difficult to make out where the gully began. The moonlight and our headtorches saved us and showed us where to stop traversing. The gully looked easy, but loose, so we tied into one rope just in case. I set off up easy terrain but was soon stumped by a hard looking groove. Not wanting to fall while simul-climbing, we belayed the section properly. I teetered up the hard section until I bumped into an ancient belay. Just when Robert was about to start seconding, a volley of rocks reminded us of our precarious position in this loose rubble. Above the groove the terrain was easier, so we simul-climbed to the notch behind the first tower. We had slowed down significantly and the sun had just risen.

Having decided that I would lead all pitches up to the ridge, I set off again. Above the belay lay an overhanging crack which blocked the access to the upper gully. With poor gear, it took a while to commit to and even then put up a good fight (maybe UIAA 5+?). It was not going to be the last time I was thankful to be wearing monopoints. The difficulties eased a bit, but didn’t stop. Another 40 meters of partly loose and hard climbing lay ahead. I got to the belay a long time later, feeling worryingly worn out. If the whole route was like this we could be here for days! The next two pitches to the notch were a hell of loose stones. With every move I was worried that I, along with several tonnes of rock, would come shooting down towards Robert at the belay.

The first chossy gully.

We reached the notch many hours after crossing the Bergschrund and were delighted to see solid granite above. The gully had already worn out our body and nerves, but we still had about 700 meters of climbing to do. We changed from boots to rock shoes and soon enough it was my lead again. The 5+ slabs were, in hindsight, probably the nicest pitch of climbing on the whole route. I still wouldn’t give it a single star… One more pitch (with a notable 30 meter run-out) by Robert brought us to the left edge of the middle snowfield. Standing on good ledges we changed footwear a second time.

The Dru, Aiguille Verte and Droites

Aiguille du Midi

Grand Combin and Matterhorn

As we had expected the ‘snowfield’ was made of black ice, so my progress was slow. Rocks were protruding from the ice, creating another obstacle. I climbed towards a slight mixed groove blocking the way to the easier top section of the snowfield. Halfway up the groove I was gripped: My crampons were smearing on granite slabs, only one axe was in a cruddy piece of ice and my last gear was a poor nut and an ancient peg a good five meters below me. Surely this was the wrong way!? I painstakingly reversed the moves and tried to climb further right. From my new vantage point I realised my mistake. It would take at least two pitches of poor ice and mixed climbing to follow the correct route and reach the same height as I was now. Though probably harder, I chose to retry my earlier ‘shortcut’ route. In the end I battled up the groove (maybe M5/6?), placing a poor peg along the way à la Scottish-winter-style and then building an unorthodox single-yellow-screw-and-double-ice-axe belay. Robert then finished off the rest of the middle snowfield. Arriving at the single bolt! belay it was my lead once again.

Robert climbing the easy section of the middle snowfield.

The pitch looked to be a rock pitch, dodging a lot of shit-looking ice. The issue was that I was still wearing crampons and there was no ledge to change shoes. We resorted to building a hanging belay from which I could change my shoes before my lead. Taking off crampons, shoes and socks while hanging in a harness, without dropping anything down the now 400 meter face was no simple task!

Once this ‘crux’ was completed I started climbing. The route description mentioned an ice gully or (in dry conditions) 4c rock climbing to its right. Due to wet, but poor ice conditions, the gully and right wall were not an option. I was being forced to climb the left side of the ice, which felt more like 5b. Though the climbing was complicated, the bigger issue was the gear. And mostly the fact that I managed to run out of it. The pitch was about 50 meters, and I was left with nearly nothing with ten meters to go. Those ten meters of icy, insecure gully climbing were rather draining! Looking at the clock after that lead I was beginning to think we would not manage to make it up and over that day. I was not looking forward to a bivy.

One of the actually named cruxes now lay ahead of us. It was the last rock pitch blocking our access to the upper snowfield. Robert took the lead and instantly got lost. We moved the belay to assess the situation together. As it turned out, the way he initially tried was correct. But it looked awful. Wet streams were running down the cracks and all of the easy looking terrain was covered in quickly-melting snow and ice. Having climbed all of the hard pitches below, I was happy to be standing at a more or less comfortable belay, watching the struggle. Robert fought upwards, across wet 5c rock, but then encountered the same gear issue I had. Down-climbing a little from his high-point, he set up an uncomfortable belay in the middle of the crux. From here, restocked with gear and rope I brought up, he made battle with the rest of the pitch. Like my pitches before, the wet and hard climbing took its time and physical toll. Even seconding was a lot more than a walk in the park.

We reached the bottom of the upper snowfield at 17:00. Yesterday, we had said that we would try to reach the summit if we got to the base of the upper snowfield at 17:00. Being there now, reaching the summit before nightfall seemed impossible. In addition to our sluggish progress hindering us from topping out, the sun on the upper slopes was now sending a lot of ice- and rockfall our way. From our current belay the whole snow slope and exit gullies seemed like a shooting range. We could forget crossing that until a good re-freeze.

Our attention now turned to finding a suitable bivouac spot. It was my turn to lead, so it was my turn to scout. I climbed the remaining five meters of semi-dry rock in rockshoes, then found a 10cm wide ledge to change back into my big boots and crampons. I had hoped changing shoes in a hanging belay was the worst I would experience that day, but now definitely was worse: My ‘safety’ was that I was clipped into 2 axes hammered into cruddy ice and I was balancing on one foot on a scrittley ledge. Each awkward mis-balance or near-fall sent a shock through my whole body. It took a good half hour to complete a task that – with a chair and nice solid ground – would take about five minutes… Once again, speed was not our forte.

From the belay Robert and I had spotted 3 different possible places. Traversing back and forth across the black ice, I eliminated one after the other. They were all either too steep or inexistant. The last remaining option was what looked like a ledge on top of a small boulder. I climbed up to find the “ledge” was not a ledge, but a solid block of ice. If we could only chop it away, we might find a ledge? By now we were not left with a lot of choice. It would have to do. The rocks around made good anchors and I thought we could get a good screw in above our heads when the sun finally set. Ledge or not, this was where we were going to bivy.

FIVE – The Bivouac

Together, we hacked at the ice slope. An hour of tedious labour and our work was finished. One downward sloping ice bucket seat and one pointy rock seat, icy back-rest included. All that was missing was an unfriendly air stewardess and it could have been Ryan Air. By now we had also established a pretty good anchor, tied together like a huge web. Unless the whole face fell down (which really did not seem that unlikely), we would be safe even if we slipped off the precarious ‘seats’. The next challenge awaiting us was getting changed. We had climbed all day in very thin base layers, but that would be too cold for the night. But how on earth do you put on thick long-johns when you’re wearing a harness and crampons. A few minutes later I had to stop to enjoy the hilarity of my situation. I was wobbling around, pants and harness around my knees, one foot in a boot, the other waving about for balance. If anyone had looked at us through the telescope at the refuge now, they would probably have called a helicopter…

Changed, we both settled down for a cold night. I was sat on my rucksack in the ice bucket, Robert, on his rucksack on the pointy rock. We were wearing all of the few clothes we had with us and our harnesses were tied to the anchor. The walls around us were now a drying rack for our soaked ropes and all of the gear, axes and crampons. The cooker we had carried with us was now furiously melting at the snow and within a few minutes we had replenished our water supplies. Thank god for my reactor stove…

Dinner time.

The comforting view.

From all the exhaustion, I wasn’t very fussed about eating anything, but knew that I had to force something down. We cooked up the one freeze-dried meal we had carried and slowly shared it between the two of us. Having finished ‘dinner’ all we could do was wait for sunrise. It was about 20:30. So far the bivy had been warm, but the sun was about to set and change everything. We unpacked the two man bivy bag and stooped it over our legs. It was awkward to sit in while maintaining purchase on the ‘seat’, so we had to readjust the bag every few minutes.

The sunset was glorious from our high vantage point. We could see from Mont Blanc du Tacul all the way to the Matterhorn. The lights of Geneva were shining far in the north and I couldn’t help but think how comfortable all those people must be. Oh well, I guess this was only my own fault. Dusk changed to night, but our situation didn’t alter much. We were both uncomfortably shuffling around, readjusting the bivy bag, trying not to slip off the ledge. Due to the icy back-rest, leaning back was too cold, so we had to do with sitting upright. Additionally, I had a small Nalgene bottle poking right into my arsecheek, cutting off the bloodsupply to my left leg. I thought about moving it, but the effort involved outweighed the benefit. Shuffle about was all I could do.

Aiguille du Midi.

The Dru, Aiguille Verte and Droites.

Ready for a cold night.

By now it was clear that we wouldn’t sleep. Every now and then Robert and I exchanged a few sentences. We would maybe doze off for a few minutes at a time, but a need to readjust would wake us. The hours dragged on slowly and I didn’t dare look at my watch. We knew it was half past one when headtorches left the Leschaux hut. The next wave of Walker ascentionists. Robert dug out a Snickers from between his coats. Midnight snack deluxe. The sugar supplied us with warmth for a some minutes. A few hours later headtorches appeared below the Aiguille du Midi: Mont Blanc ascentionists. It was now well past 02:00 and it was bitter cold. We shared a powerbar which did the same trick as the Snickers, but was a bit more effective. Some time later headtorches appeared outside the Leschaux hut once more: Petites Jorasses ascentionists. I was uncomfortable, tired and freezing.

I could go one about the next hours of the bivy, but it was really just the same. Our 5am alarm seemed endlessly far away.

SIX- Day 3

05:00 and we were keen to get up. We were cold and stiff and hadn’t slept more than an hour in total. Breakfast was some powerbars. Cooking would’ve been to complex. It took a while to get climbing-ready and dismantle the bivy, so I only started leading the upper ice field by 07:00. Unlike the middle one, this ice field was luckily just a calf-burner. From the top a long gully branched off left. In good conditions the gully was meant to be 70° and M4. Once again, we didn’t find good conditions: Roberts lead was slow, run-out and difficult. The gully above the belay continued for quite some length, but also looked a lot easier than below. I led off and told Robert to second once the rope ran out. Although the gully was easier, I felt like I was climbing on egg shells. Every piece of rock was loose, gear was nearly inexistant and the climbing was not a piece of cake. Not only did I have to watch that I did not kick off any stones – potentially hitting Robert – but I had to make sure the rope didn’t pull off anything either. It was only my second lead of the day, but those 80 meters of simul-climbing really drained me. Perhaps being at 4000m was also starting to show.

Top of the upper icefield.

Lifegiving rays of sun.

Another chossy gully.

We had reached the upper col and now had the best part of 5 pitches left to the summit. We could see the people doing the Jorasses-Rochefort traverse as silhouettes on the skyline. I knew the last pitches were the crux, and was worried about the last 20 meters that the french had described at the hut. Would we really end up not finishing the route after all this? I could only hope.

Feeling the altitude more than myself, Robert slowly led the easy and solid ground to the next belay. Above this lay a ramp of choss. Only perhaps grade 2/3, but nothing seemed to be attached to the mountain. From here, we had the choice of exit routes. Earlier, I had seen that the right ice chimney was partly formed. There was an in-situ belay at its base and I would not have to cross much of the choss ramp to get to it. I crept across and had a thank-god moment when I grabbed a hold of the belay. Unfortunately, the ice chimney seemed much too thin. It was unclimbable. Shit.

I lowered off the belay, pulled the ropes, re-tied, and reversed to Roberts position. The other two exit routes went straight across the ramp. I had no choice. Shit. Taking my time I climbed a whole 50 meter pitch with one poor cam. Compared to the ramp, the old sling belay I found seemed like a tank. To let him rest a little and take the altitude strain off of him, I told Robert I’d be block leading. Part of me also wanted to conquer this loose section. Our topo distinctly described the next pitch as “loose”, but it turned out to be good quality rock compared to the ramp. I guess the ramp is normally covered in névé. I had now reached the point where the two left exits split. The mixed ramp to the far left seemed thin, void of gear and difficult. It was probably climbable, but perhaps the original exit through the rock was a better option. Directly above the belay, an old peg led the way. The terrain was steep, lichen-y and loose, so, after trying, I came to the conclusion that was the wrong way.

Back at the belay I reconsidered our route. The mixed ramp still seemed like the last option. We were stood on the left hand side of a tower and I was sure the next belay was on the tower. I knew there was a gully to the right of the tower, so maybe if I could reach that… A small ledge led to the right side of the tower. The left hand side of the gully was climbable in rock shoes (we had changed once again) so I made steady progress. I found a new looking peg which encouraged me in my decision. In the end, the next belay was indeed on top of the tower, though the route I took to get there may or may not have been the correct one. We were now a mere 60 meters below Point Croz.

Robert was feeling better, and I was feeling worse, so it was his lead. The swap came at a perfect point. Above lay the 6a crux pitch, I was feeling worse for wear and Robert was a stronger rock climber. After a fair amount of faff he headed upwards. The pitch was loose, but Robert cruised steadily upwards. Nearing the 50 meter mark we ran into trouble. Robert had once again run out of gear, there was no suitable belay in sight and the rope was not long enough to make it to the summit. Searching for something to belay off of, Robert climbed around for some time. A while later he had built something on what ever gear he had left. His remark to climb carefully when I started seconding wasn’t much of an encouragement. After an initial near-miss when a foothold broke, the pitch was steady. Arriving at the belay I could only confirm what I had been dreading. The belay was fairly shit. The summit seemed within reach, but – more worryingly – so did the ground 1000 meters below. The route had wound its way back to the left side of the spur and we were now more or less directly above the Bergschrund. It was the first time that there was a serious amount of exposure!

Although earlier I had assumed that I was done leading for today, it was now my turn to take us to the summit. Swapping the lead back to Robert at this belay was impossible. A steep groove led to the top and, like the rest of the route, it was chossy. I spotted some key holds, but was sure they would snap if I weighted them. I was convinced this was where the French had to be rescued. After some faff, I decided I would only be able to finish the groove backpackless, so hung my burdening pack on the only good bit of gear around. Now nearly weightless, I committed to the sequence of detached looking holds. They held. Had it been a few degrees warmer, I am sure the rock would’ve snapped. A few more moves and I reached a col just five meters to the side of the summit. I was on top of the Grandes Jorasses after having climbed the Croz spur. I could not believe it. It had seemed impossible, even just five meters below the summit.

The north face to our left, and the notch into which we topped out.

I was exhausted. It was 14:30 on Wednesday. We had been on the go non-stop since 1:30 on Tuesday (I’m not counting the bivy as rest) making it a 37 hour effort of which 35.5 hours were spent in the vertical world. My hands were a battered, bloody mess and I could barely hold things. My feet were sore and swollen and my back ached from the terrible bivy and heavy backpack.

Summit of Point Croz, 4110m.

We scaled up to the summit and solemly savoured the moment. My 20th 4000m peak in the alps. Irrelevant. The weather was perfect and our view reached all around the alps. Mont Blanc, the Peuterey Integral, Grand Capucin, The Dru, The Droites. Sadly the right and higher section of the Grandes Jorasses blocked our view towards the east. We were now back in the sun, which began to boil us under all of our warm clothes. The need to change and relax a bit was dire, luckily the south side of the Grandes Jorasses is much more favourable. Finally, we could take off our harness without fearing death. I can’t say I was particularly stressed in the wall, but the other side was definitely much more relaxed.

The descent from Point Croz.

The descent from Point Croz.

Haggard summit selfie.

The descent dragged on, but wasn’t too complicated compared to the ascent. A series of abseils took us down to the glacier, which we crossed towards a rock ridge. Now being on the normal route, route finding and climbing was easier. We down-climbed and abseiled that towards the lower glacier. This then brought us to the rock just above the hut. A few more minutes of walking and we reached the Boccalatte hut. At 18:30 we stumbled onto the terrace of the tin shed.

I was wrecked. Generally all of my body was aching. I thought I was fit, but now felt very much the opposite. The huts guardian – a guide himself – came out and congratulated us. He cooked us food and told us to feel right at home, since “this is a hut and not a hotel.” What a welcome! Robert and I ordered two beers, but opening the can turned into the crux of the day. Our tips were so thin that we had to resort to using a knife. Says something about our state.

The food went down slowly, but was very much welcomed by our starved bodies. We then fell into bed and were out cold within a minute.

SEVEN – Day 4

A resupply helicopter at 07:00 woke us, so we dragged ourselves to breakfast. The hut had filled up overnight, with several teams coming down from Walker Spur in one day ascents. The mood at breakfast was such a contrast to that at the Leschaux hut. Only while speaking to all of the other climbers did our achievement sink in. The Croz Spur really is quite something!

We had climbed an incredible route in poor conditions. We had covered hard, insecure and loose ground. We had pitched almost all of the spur and had suffered through an uncomfortable bivy. And most of all we had made it. Later Robert said he thought it much more difficult than the Walker Spur and possibly the most difficult route he has done. I can imagine that the Croz Spur is quite a good route in winter – all of the choss would be frozen in place and all of the gullies would be ‘runnable’ – but sadly, we climbed it in summer. Now I can’t recommend it at all.

After breakfast, we descended towards Italy, already planning the next big trips. The Peuterey Integral was looming across from the valley, but there are of course many other routes across the alps. We took a bus to Courmayeur and then another to Chamonix. Coming out of the tunnel in Chamonix I spoke the ridiculous words that were on both our minds: “Hey, if the weather is good, do you fancy doing something chilled tomorrow?” Who needs rest days…